Version 3.1

For model descriptions, please see the P-R webpage

1914 Rauch & Lang J-4 Duplex Drive Coach

Rauch & Lang is German for smoke & long, an ironic name for cars that emitted no fumes and had limited range. The company was predominantly run and financed by the sons of German immigrants, which made up 40% of Cleveland’s population in 1900.

Of the well known early electric cars, Rauch & Lang developed a reputation for having the finest coachwork.

Jacob J. Rauch set up a blacksmith shop called the West Side Smithy on Columbus Road in 1853. He grew the business from shoeing horses, metal forging, and repairing wagons, to include manufacturing vehicles. His 15-year-old son Charles Rauch Joined the company in 1860, and they relocated to the more heavily traveled West Pearl Street (now West 25th Street), just over a block from the popular Westside Market and about a mile from the Ox Bow Bend in the Cuyahoga River. A buggy builder was like a furniture factory with a blacksmith out back, preferably in a separate building. Jacob did not live to see the transition into luxury coach building, as he died only ten years after he started his company. The Civil War, which Killed Jacob at Gettysburg in 1863, helped transform Cleveland into a great industrial center.

On January 8, 1878 Charles E. J. Lang joined the company as bookkeeper, and, in 1885, he bought a quarter interest for $75,000. Lang’s father owned the popular Market Saloon at 86 Lorain Street. Lang’s in-laws, Fred & Katherine Schweitzer, made a fortune in Cleveland’s real estate boom.

In 1885 the partners incorporated as the Rauch & Lang Carriage Co, with Charles Rauch as President and Charles E. J. Lang as secretary and treasurer. Henry Heideloff, Herman Kroll, and John Kreifer filled out the board of directors. Lang & Rauch had salaries of $1,800 per year while the other directors drew $1,000 each. They leased a modest factory building on West Pearl Street for $1,650 per annum, employing 40 men & 3 minors.

With the influx of Lang’s capital and his management skills; work shifted from wagon repair, with some manufacturing, into being a full-fledged wagon and carriage company, which did most work in-house, except tanning and weaving. In 1888 the company re-formed with capital stock of $100,000, and they built the business into a leading maker of buggies and fine carriages in the region. The Company built their first permanent factory, consisting of two buildings on either side of the alley which bisected the block. To the west of the alley, they built a two-story/four-story factory, with a footprint of 32’ x 64’, at 2164 and 2168 West Pearl Street. It was an attractive building designed by Bohemian immigrant Andrew Mitermiler, featuring brick piers with cut stone footings and accents. A glass-front showroom was at the sidewalk facing Pearl Street. The first two stories filled both lots, while the third and fourth floors covered about two thirds of the footprint.

Offices were on the ground floor, storage on the second, painting and varnishing on the third, and polishing on the fourth. Heating was from the basement, delivered through ducts in the piers.

This building was joined by a tunnel in the basement, and an enclosed ramp on the second floor, to the smaller four-story “L” shaped sister factory built across the alley to the east side. It also had a full basement, housing four drying kilns and lumber storage. This building was also 64’ deep, but only had 18’ of frontage on Pearl, with 37’ extending along the alley, where an 18’ wide section wrapped behind the original single-story building. In 1900 an addition was made at the far eastern end of this factory complex, with a forge and blacksmithing on the first floor.

In 1902, a year after Elmer J. Lang joined his father’s company, becoming sales manager, Rauch & Lang had success selling Buffalo Electric cars from their carriage showroom. They decided to make their own brand of electric carriages the following year and built a prototype with motors and controllers from the nearby Hertner Electric Co. Production began in 1905 with a Stanhope. They added coupés and depot wagons, selling about 50 electric vehicles in the first year.

The initial series of cars were of the conventional single motor design of the time, turning jackshafts with a differential at the center, driving the rear wheels through twin chains. This design had a light rear axle, isolated from the driveline mass, with the wheels rotating at the ends. The chassis & mechanical parts were from outside vendors. They seemed to go out of the way to avoid components used by their established cross-town rival Baker.

In 1906 Hertner appeared to be gearing up to make their own electric car, and published an elaborate brochure with drawings and descriptions, probably intended for prospective investors. Rauch & Lang management had decided that motorcars were their future, and that carriage trade customers would prefer the quiet reliability of a battery electric to the messy, unreliable, gasoline alternative, especially for enclosed cars where there were windows to rattle.

The way forward was to buy the Hertner Electric Company and add a new metal fabrication factory to the coach building shops and old smithy. This allowed them to make almost everything in-house; manufacturing complete rolling chassis on which to put their luxury bodies.

Charles L. F. Wieber inherited a merchant tailoring company and built it into the largest of its kind west of New York. He was brought in as a new partner. Wieber was associated with Lang’s in-laws, as president of the Lakewood Realty Co. With his investment, Rauch & Lang was recapitalized at $175,000.

After the buyout, John H. Hertner, and his chief engineer De Witt C. Cookingham, ran the motor vehicle division. Electrical components were continued to be made at the Hertner factory. The new factories on the side of the alley facing 26th St. were for metalwork, and the buildings facing 25th were the offices and woodworking factories.

Horse-carriage manufacturing went down by 75% and wagon repair work by 80%; except for heavy trucks & refrigerated wagons (with polar bears painted on the sides,) which went up by 30% for the next two years.

Cleveland renamed east-west streets with numbers in 1906; West Pearl St. became West 25th St.

Employees could arrive at the factory by the electric trolley cars running on W. 25th Street.

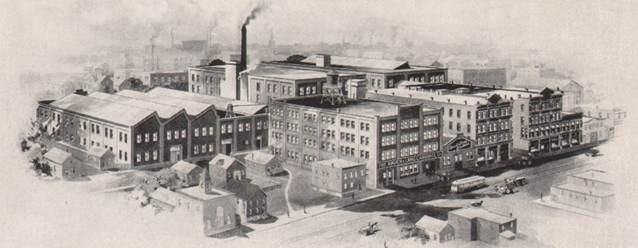

Rauch & Lang Factory on West Pearl Street, Cleveland

William “Billy” Neumann, One of Detroit’s most successful car dealers, with Pierce-Arrow and Chalmers gasoline cars, became the dealer for Rauch & Lang, at 1342-1352 Woodward Avenue.

1907-1911 was a period of rapid expansion.

They constructed three new factory buildings on the land directly across the West 25th Place alley, fronting West 26th Street. The factory campus grew to seven buildings, some contiguous, and some separated by the alleys bisecting the block in both directions.

Most of the coachwork was done in the amalgamated buildings along 25th Street. The new 26th St. factories covered more land than the 25th St. buildings, with street numbers ranging from 2161 through 2203.

They initially built a four-story building of 38’ x 64’ designed by the Osborne Engineering Co. The first floor had an Iron and steel shop, the second a stock room, the third had upholstering, and the fourth was for polishing and paint drying.

It was connected to the original Pearl (25th) Street factory by an enclosed bridge, three stories up, over the alley.

They also constructed a 60’ x 64’ two-story building further to the east, housing a metal works and power plant, which was walled off in brick. It had with three coal-fired boilers powering a pair of 250 hp steam engines driving dynamos. Smoke from the boilers was vented through a 90’ tall brick chimney placed against the wall of the four-story factory. The entire second floor was taken up with a machine shop. Machine tools were driven through shaft and belt systems by large electric motors in each work area.

The main part of the first floor was used for assembly of the platforms, with a steel fabrication shop tucked into the southwest corner. A freight elevator and stairs went up through the two floors on the outside of the contiguous four-story building, giving access to all floors of both buildings.

In 1908 Rauch & Lang opened a fancy new showroom at 623-631 Superior Avenue, near Cleveland’s town square.

In December of 1909 they reincorporated at one million dollars.

The metalworking facility was extended further east along W. 26th St., doubling the metal-craft floor space. Across the short alley, to the west of the four-story factory on W. 26th St., they built a similar 38’ x 64’ four-story building with the stairs & elevator on the inside. At street level was a garage and charging room, on the second floor was electrical testing, the third floor expanded the trimming and upholstery space, and the fourth was for varnishing. It was connected to the eastern and northern buildings across the alleys by two enclosed bridges at the third-floor level.

Before the introduction of solvent-based lacquer in the mid-1920s; paint coatings, especially color, took a long time to dry. A good deal of interior factory space was taken up with paint and varnish drying on nearly complete vehicles. The finishing six coats of varnish were applied over a period of fifteen days. Ads stated that each car took three months to build and trim.

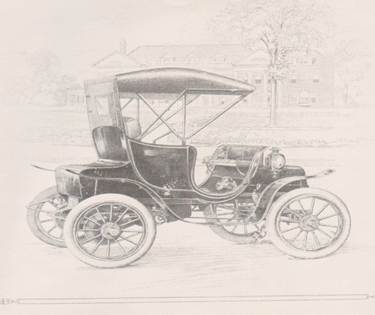

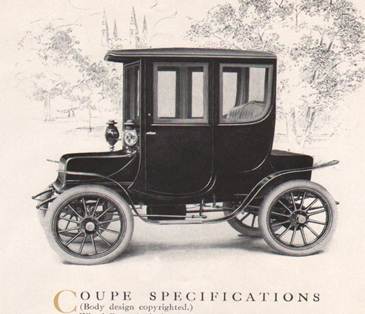

1910 Stanhope (left) and 1911 Coupé (right)

With the 1911 models Rauch & Lang introduced shaft drive, employing a straight-cut bevel ring and pinion gear rear axle unit made in their own machine shop.

This setup was similar to the one used on Baker Electrics, which located the rear axle in shaft drive cars by a method of attaching the leaf springs to the frame which kept the rear axle in alignment with the motor and frame without the need of reach rods or a ridged driveshaft tube, such as that used in Ohio Electrics of the time. All models were available with either chain or shaft drive. The Stanhope was equipped with a 48-Volt battery. Victorias, Coupés, & Broughams were available with either 48-Volt or 80-Volt batteries. Shaft drive or the larger battery option each added $100 per car. Prices ranged from $1,900 for the 48-volt chain drive Stanhope to $2,800 for the 80-Volt shaft-drive Extension Coupé (later called a Brougham.) The battery was in series at all speeds, with a continuous torque controller.

Electric braking was standard on all models, and a backwards pull on the controller handle actuated both dynamic electric braking and a mechanical brake, while disconnecting the battery from the motor circuit. A foot-pedal “emergency” brake operated roller cam actuated expanding internal shoes at both rear wheels. The sidelights had special reflectors to “eliminate” the need for headlights; the ceiling lights had Holophane lenses. The advertised range was 50-150 miles depending on battery, speed, and road conditions. There were other options; an ESB “Ironclad” or the Edison alkaline battery, were available at additional cost, as were Motz cushion tires.

Rauch & Lang Coupés had reached their classic phase; the bodies would remain similar for the rest of their history.

In 1911 the original wood frame building was demolished and a new 46’ x 30’ four-story factory was built, filling in the gap between the newer four-story factories on West 25th.

The Baker Motor Vehicle Company filed an infringement suit based on Emile Gruenfeld’s rear axle suspension patent.

In 1912 Charles Rauch died, and Charles Wieber became president. Charles E. J. Lang was VP & treasurer. Francis W. Treadway, who was Lt. governor of Ohio from 1909 to 1911, joined the company. He was a graduate of Yale Law School, who became state senate president, and was a close friend of Warren G. Harding. He would eventually become Baker R & L president.

About five hundred cars were made in 1912, compared to seven hundred Bakers and slightly over a thousand Detroit Electrics. The new inside-drive Broughams were available with lever steering from the rear bench seat, or wheel steering from the left front seat.

In 1913 R & L built a new 21,700 square foot factory on West 26th Street, 85’ x 64’ in area and four stories tall, of brick and steel construction. A freight elevator was at the far west end of the building to facilitate potential expansion to the end of the block. Further expansion became redundant when they merged with Baker two years later, giving them all the additional factory space they would need.

1913 Rauch & Lang R-3 Roadster

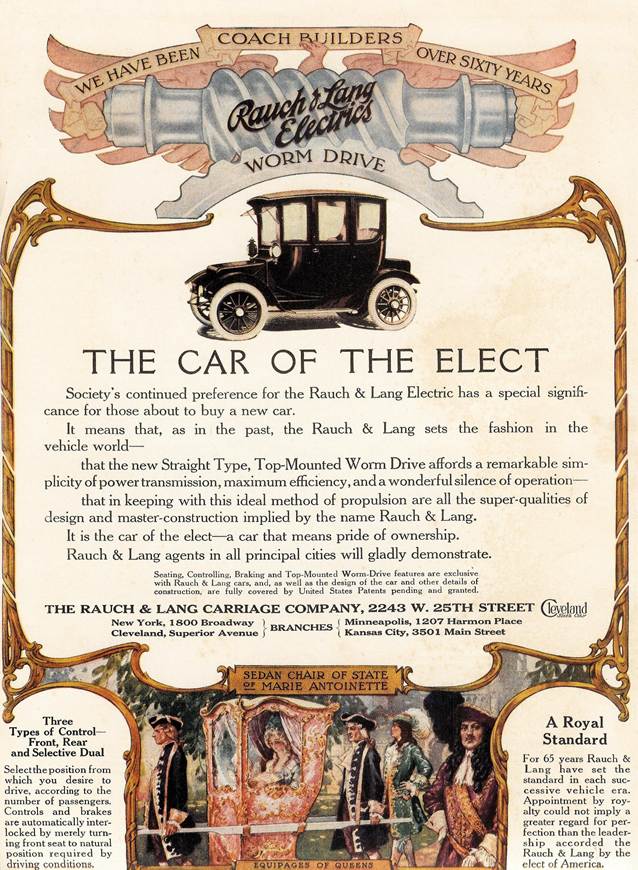

Rauch & Lang dropped the noisy, less-reliable, straight-cut bevel drive gears, and adopted a worm-gear drive. Introduced July of 1913 in the prestiges J-4 Coach models, and then for all seven 1914 models. The cars were advertised as being “faster than the law allows.” Body styles included a three passenger Roadster, available with a Coupé top or a faux radiator, and Broughams in three sizes, accommodating four or five passengers. For those with a staff chauffeur they made a Town Car, with wheel steering in front of the cabin. Prices ranged from $2,600 for the basic Roadster to $3,800 for the Town Car. The Broughams had interior lights that lit when the doors were open, and a cigar lighter. The doors still had lift up windows, with a strap. The Victorias, once popular for social summers in posh resort towns, were phased out in favor of the “electric hood” Roadsters, which were slightly larger and had doors.

Roland S. Fend, then staff engineer at Woods in Chicago, designed a duplex drive system for R & L, as did in-house engineer De Witt Cookingham, which was also incorporated into the J-4 “Coach” model. The two patents were not enough to prevent a lawsuit from Ohio Electric, which had been the first to introduce duplex drive. They claimed previous art in Fay Farwell’s 1903 patent.

Ad For 1914 Rauch & Langs, Featuring the New Worm Drive

On June 1st, 1915, the Rauch & Lang Carriage Co, with a capitalization value of $1 million, merged with The Baker Motor Vehicle Co, valued at $1.5 million. The new company was called Baker Rauch & Lang. The reasons given for the merger were to consolidate the manufacturing, marketing, and advertising costs. They intended to become the dominant electric carmaker, but war intervened.

Charles Wieber president, Frederick White 1st VP, Charles E. J. Lang 2nd VP, R. C. Norton treasurer, and George H. Kelly secretary. F. W. Treadway remained as counsel, and Rollin C. White, who had just celebrated his 78th birthday, was a director. The Whites, Norton, and Kelly were from the Baker side.

The merged company sold two models of the lighter Baker style Coupé through 1916, after which the brand was retired for pleasure cars, living on with the growing industrial vehicle business.

Walter Baker & Fred Dorn stayed with the American Ball Bearing Co side of the split.

In late 1915 General Electric invested $2 million in the Baker R & L Company, getting seats on the board for Anson W. Burchard (VP of GE), D. C. Durland, and Richard H. Swartout. In February of 1916, some of the new funds were used to bring the Owen Magnetic Car Company into the mix, with Raymond Owen becoming VP of sales.

The Edgewater Park Baker factory manufactured the Owen Magnetic platforms, and the bodies were made at the R & L plant. The Fort Wayne facility of General Electric continued to make the Entz type electric drive units. GE used some of the technology to develop systems for diesel electric locomotives.

In August of 1917, Charles E. J. Lang left Baker R & L to start an independent business called the Lang Body Company, with his son Elmer J. Lang.

After World War II, the company fractured into separate pieces. Baker Rauch & Lang retained the industrial truck and contract body building parts, while spinning off their interest in electric cars. The Owen Magnetic business returned to R. M. Owen. He made some cars in Wilkes-Barre Pennsylvania for a few more years.

Baker Rauch & Lang was reorganized in 1919, with a body division using the Raulang brand, and an electric industrial vehicle division under the Baker brand.

Electric pleasure cars retained the Rauch & Lang name.

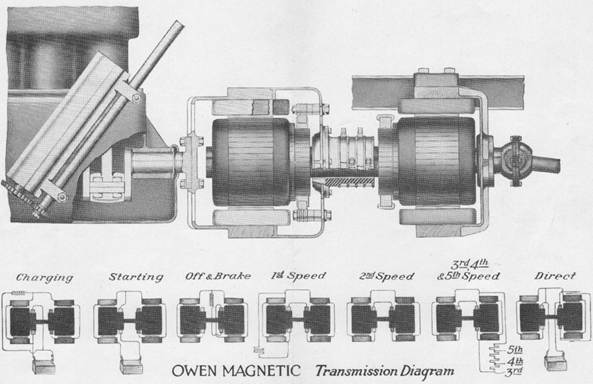

Owen Magnetic Transmission Diagram

Harry H. Doering, head of sales at the Philadelphia branch of Rauch & Lang, had been elevated to sales manager for the entire Company.

Doering saw an opportunity to own one of the most respected luxury car brands, and started enlisting successful dealers to buy the company.

On January 6th 1920, the electric car business was sold to the coalition of Rauch & Lang dealers that Doering put together.

They set up production next to the Stevens-Duryea factory in Chicopee Falls Massachusetts, which had recently been acquired by Ray S. Deering, partner in a Chicago electric car dealership with Paul A. Frank, who became Rauch & Lang Incorporated’s president.

The move was pitched to the press as a way to increase production, claiming there was a shortage of skilled workers and commodities in post war Cleveland.

In January of 1920 R. S. Deering was mentioned by a few trade publications as “buying” Rauch & Lang. He was likely to be influential in the choice of re-location, and helped with the deal, but no contemporaneous document (including stock & business filings) mentions him as an officer or director of Rauch & Lang Inc. The similarity between the names Doering and Deering probably contributed to the confusion.

Management gelled with Frank as president and Doering as VP of sales and advertising. Nathaniel Platt was VP in charge of New York sales and worldwide exports.

On March 4th, 1921 the new factory was put into operation. It was a one-story brick structure, with a nine-section saw-toothed roof, 300 by 320 feet, slightly less than 100,000 square feet of well-ventilated, electrically lit, floor space, at a cost of about $350,000. Platforms were manufactured at the new plant, while the classic Brougham bodies continued to be made by Raulang in Cleveland. The nearby Chicopee Falls satellite of the Springfield Coachworks made a small number of more contemporary looking cab bodies.

The plant was said to produce about eight cars a week (400 annually). They announced plans to produce 1,800-2,000 units per annum with 800 workers.

As so few of these cars were registered or remain, compared to those produced from 1914-1919, this pace was clearly not met. Serial numbers suggest only around 60 new classic Broughams were made.

They opened business into the headwinds of the 1920-1922 post-war recession, with a decline in business activity of more than 28%.

Inflation initially peaked in November of 1918 at 20.7%, with an even higher peak in June of 1920 at 23%. After that, rates fell off dramatically. January of 1921 through February of 1923 was a period of disinflation, dipping to -15.8% in June of 1921. This was an all-time record, not even matched during the great depression of the 1930s.

Rauch & Lang Inc. went into receivership September 24, 1923. The assets of both Stevens-Duryea and R & L Inc. were sold to the rather persistent Raymond Owen for $446,857.28. The bundling of these assets does suggest shared ownership. Beginning August 25, 1925, Owen made a few more electric and magnetic transmission cars under the Rauch & Lang brand, putting Robert W. Stanley back in charge of R & L Inc. These companies all failed in 1932.